Listen Full Story:

Read Full Story:

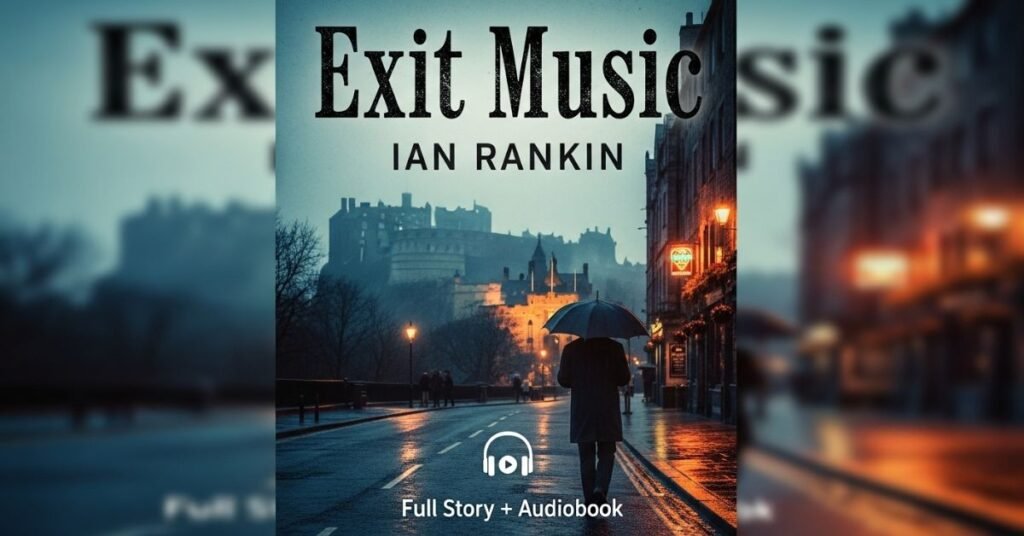

It was late autumn in Edinburgh, and the cold air carried the smell of wet leaves and wood smoke. Detective Inspector John Rebus knew his time was running out. After decades on the force, his retirement was only ten days away. But endings never come quietly, and Rebus, as usual, found himself caught in the middle of something that refused to let go.

It began one night when a body was found in a dark alley just off King’s Stables Road. The dead man was Alexander Todorov, a Russian poet who had come to Edinburgh for a cultural exchange program. At first glance, it looked like a mugging gone wrong. His wallet was missing, his head was bashed in, and there were no witnesses. But to Rebus, something felt wrong. The injuries were too deliberate, too personal. There was no panic, no haste — only quiet precision.

Detective Sergeant Siobhan Clarke, Rebus’s longtime partner and friend, was now effectively taking over his duties as he prepared to leave. She had the patience and diplomacy that Rebus lacked, but she also understood that his instincts were almost always right. Together, they started digging into the poet’s life. Todorov wasn’t just a visiting artist; he had friends in high places, including some of Scotland’s wealthy businessmen and politicians who sponsored the arts. And among those names appeared one Rebus knew all too well — Morris Gerald “Big Ger” Cafferty.

Cafferty was a powerful crime boss who had shadowed Rebus’s entire career like a dark twin. He was officially retired from his criminal empire, but Rebus didn’t buy it. Wherever there was corruption, money laundering, or quiet intimidation, Cafferty’s fingerprints always lingered somewhere in the background. When Rebus heard that Cafferty had attended one of the cultural receptions involving the dead poet, his suspicion hardened.

At the same time, Siobhan was dealing with her own rising responsibilities. The department wanted her to step into leadership after Rebus’s departure, and she had to manage the politics of ambition and loyalty. Meanwhile, a second death pulled the case in a darker direction. A sound engineer named Rory McCulloch was found dead in his car, an apparent suicide — engine running, fumes filling the vehicle. But the evidence was too neat. Rebus saw connections that others ignored. McCulloch had worked in a recording studio owned by a businessman named Andropov, a Russian expatriate with ties to wealthy Scots and rumors of organized crime.

Rebus and Clarke started piecing together the pattern. The Russian poet, the businessman, the sound engineer — all seemed tied by invisible threads of influence, corruption, and silence. The cultural exchange that had brought Todorov to Scotland wasn’t simply about poetry and friendship between nations. It masked a deeper game involving money, bribes, and possibly the quiet elimination of those who knew too much.

When they visited Andropov’s mansion, they found themselves in a world of polished marble and hidden menace. The man was smooth, charming, and untouchable — exactly the type Rebus despised. Every question they asked was met with polite evasion. Rebus could feel the wall closing in, but his retirement meant his authority was slipping. He wasn’t supposed to be taking risks anymore, wasn’t supposed to be kicking down doors or threatening gangsters. But he couldn’t let it go.

Then, in one of the most unexpected moments, Cafferty invited Rebus to meet him for a drink. The two men sat facing each other like old wolves, acknowledging that time was catching up to them both. Cafferty hinted that the Russians were making moves into Scottish territory — investing in property, manipulating politicians, and laundering money through legitimate businesses. He didn’t say he was involved, but he didn’t deny it either. And when Rebus pressed him about Todorov’s murder, Cafferty smiled with that half-friendly, half-dangerous grin and told him to “enjoy retirement while he still could.”

Meanwhile, Siobhan followed up on the suicide case. The toxicology report showed drugs in McCulloch’s system that didn’t fit with his supposed depression. His last recordings also revealed a strange audio clip — muffled voices, a scuffle, a woman crying out, and then silence. The file had been partially deleted but recovered by forensic technicians. The timestamp placed it roughly around the night Todorov was killed.

The deeper they looked, the more the two cases intertwined. It appeared McCulloch might have recorded something incriminating — perhaps a meeting or a killing. If he had tried to blackmail someone, that could have sealed his fate. The pattern was clear to Rebus: Todorov had died because he knew too much, and McCulloch had died because he had evidence.

The investigation led them into Edinburgh’s political underbelly, where Russian money and Scottish greed intertwined comfortably. They found links to businessmen funding cultural events, politicians turning a blind eye, and hidden accounts transferring cash offshore. But as usual, the closer they got, the more resistance they faced. Orders came from above to “wrap it up,” suggesting that people in power didn’t want the case to continue.

Rebus, being Rebus, ignored them. He followed a hunch to a secluded property outside the city where McCulloch had occasionally worked. There, he found traces of a third person — possibly a woman — who had been staying there. The place had been wiped clean, but in a drawer he discovered a burned piece of sheet music, on which someone had written a few cryptic lines in Russian. Later translation revealed it to be part of a poem — Todorov’s unfinished work, speaking of betrayal and truth buried under silence.

That night, Rebus received a threatening phone call. A voice warned him to stop asking questions, or retirement might come sooner than planned. He knew it wasn’t an idle threat. His car had already been followed twice. Siobhan urged him to stay back, but Rebus’s stubbornness was legendary. The thought of walking away while someone was getting away with murder was unbearable.

Soon, things escalated when Cafferty was attacked. He was found unconscious in his home, beaten badly but alive. Rebus was among the first to arrive, summoned by Cafferty’s driver. The attack looked professional — not random street violence. It was a message. Rebus demanded answers, but Cafferty only whispered, “It’s the Russians… they think I crossed them.” That admission tied everything together. The same people behind Todorov’s death were now cleaning up anyone who stood in their way.

Siobhan and her team traced a financial trail that led to Andropov’s associates. They found that one of them, a Scottish businessman named Charles Riordan, had arranged security for the Russian delegation and might have orchestrated the cover-up. Surveillance footage eventually showed Riordan’s car near both murder scenes. But Riordan had friends in high places, and the case stalled under political pressure.

Rebus confronted Riordan himself. It was reckless and unofficial, but he couldn’t resist. They met on a bridge over the Water of Leith, the city silent except for the wind. Rebus accused him directly — of murder, of corruption, of betraying everything Scotland stood for. Riordan laughed it off, confident that evidence and power were both on his side. But Rebus saw the flicker of guilt in his eyes. It wasn’t a confession, but it was enough to know the truth.

Later that night, Rebus’s car was sideswiped near his flat. He barely escaped with minor injuries. The message was clear: stop digging. But now, with his badge nearly gone and his pride burning, he had no intention of stopping. Retirement would come, but not like this.

In the final days of the case, Siobhan managed to get a search warrant for McCulloch’s studio. Hidden behind acoustic panels, they found a second drive containing the complete audio file. When played, it revealed the sound of two men confronting Todorov — one speaking English with a Scottish accent, the other in Russian. There was the sound of a struggle, a blow, then silence. And finally, a calm voice ordering, “Clean it up.” The voice was unmistakably Riordan’s.

But before they could bring him in, Riordan was found dead in his own home — an apparent heart attack, though Rebus didn’t believe it for a second. Too convenient, too timely. It felt like the Russians had taken care of their problem. The case, officially, was closed with no arrests and no clear culprit. The department was eager to move on, the media had lost interest, and the files were sealed under “national security” provisions.

Rebus spent his final day clearing out his desk. The office that had once been filled with smoke, files, and arguments now looked painfully empty. Siobhan came by to see him off, telling him that the case would remain open in spirit, even if not on paper. He smiled faintly, knowing she was the future of the force — sharper, cleaner, more political — but he also knew that justice was often something murky, imperfect, and half-won.

That evening, he stopped by Cafferty’s place one last time. The old gangster was recovering, sipping whisky and watching the news. They shared a moment of weary understanding. Cafferty told him that the city would go on as it always had — corrupt in corners, beautiful on the surface. Rebus replied that maybe so, but at least now the devils had faces. They sat in silence, two relics of an older Edinburgh, both too stubborn to change.

When Rebus finally walked out into the night, the city lights flickered across the damp cobblestones. The air was cold, but the sky was clearing. He paused by the car, looked back at the police station one last time, and lit a cigarette. He didn’t know what the future held — only that he wasn’t built for quiet endings. Somewhere in the city, someone was always lying, always killing, always getting away with it. And maybe, just maybe, he’d still find a way to keep chasing them.

As he walked away, the faint echo of footsteps followed him into the dark, the sound of a man who refused to fade quietly from a world that had never been clean. The case of the Russian poet, the recordings, the money, and the blood would all fade from headlines, but not from his memory. For Rebus, every ending was just another story waiting to begin.